دانشنامه آزاد ۴ زبانه / εγκυκλοπαίδεια / licence

Elton پروژهای چندزبانه برای گردآوری دانشنامهای جامع و با محتویات آزاد استدانشنامه آزاد ۴ زبانه / εγκυκλοπαίδεια / licence

Elton پروژهای چندزبانه برای گردآوری دانشنامهای جامع و با محتویات آزاد استدرباره من

روزانهها

همه- کانون تبلیغات آریا تبلیغ پیامهای تبلیغاتی خود را به دست نیم میلیون ایرانی در سرتاسر دنیا برسانید

- my profile Sepehr elton

- مدیریت دانش نامه سایت مدیریت دانشنامه

پیوندها

- لیستی از 7299 زبان و لهجه جهان

- Farsi <-> English Dichtionary

- 1ου Γυμνασίου Χαλανδρίου

- ابزارهای وب فارسی است

- سلامی چو بوی آشنایی

- استکهلم و استکهلمیان

- way dont you smile ?

- You tube video

- BBC Languages

- Iranian media

- اخبار سیاسی

- خیالی نیست

- دین زرتشتی

- ایران امروز

- Tv of Iran

- my profile

- kala post

- Just MP3

- 3Jokes

- irlearn

- مهتاب

- BMW

- طنز ۲

- سایه

- طنز

دستهها

- ........علوم ریاضی و طبیعی...... 1

- آمار / Statistics 4

- بوم شناسی / Ecology 3

- ریاضیات / Mathematics 4

- زیست شناسی / Biology 6

- ستاره شناسی / Astronomy 4

- شیمی / Chemistry 4

- علم بهداشت / Health science 2

- علم زمین 1

- جغرافیا 1

- علم کامپیوتر 1

- فیزیک / Physics 4

- آموزش 2

- ارتباطات / Communication 3

- پزشکی / Medicine 5

- بازرگانی / Trade 2

- حکومت / Government 2

- ترابری / Transport 3

- حقوق 1

- روابط عمومی / Public relations 3

- سیاست / Politics 2

- خانه داری 1

- علم کتابداری و اطلاعات/Library 2

- فناوری / Technology 3

- کشاورزی / Agriculture 2

- معماری / Architecture 2

- مهندسی / Engineering 2

- مهندسی نرم افزار/Software engine 2

- اسطوره شناسی / Mythology 3

- اقتصاد / Economics 3

- باستان شناسی / Archaeology 4

- تاریخ / History 4

- تاریخ و علم فناوری 3

- جامعه شناسی / Sociology 1

- فلسفه / Philosophy 3

- مردم شناسی/Anthropology 3

- آشپزی 1

- اپرا / Opera 2

- ادبیات / Literature 3

- اینترنت / Internet 3

- بازی ها / Game 3

- باغبانی / Gardening 2

- تئاتر / Theatre 3

- تفریحات / Recreation 2

- تلوزیون / Television 3

- تعطیلات 1

- تفنن / Entertainment 2

- رادیو 3

- رقص / Dance 1

- سرگرمی ها / Hobby 2

- سینما / Cinema 3

- شعر / Poetry 3

- صنایع دستی / Handicraft 2

- طراحی و هنرهای بصری 1

- کلاسیک / Classics 2

- گردشگری 1

- مجسمه سازی 1

- مذهب / Religion 3

- موسیقی / Music 3

- نقاشی / Sport 1

- ورزش 3

- علوم سیاسی / Political science 2

- زبان شناسی 1

- کشورها. / List of countries 3

- زندگی نامه ها / Lists of people 1

- راهنمایی فرار از سانسور اینترنت 1

- راهنمای ساخت وبلاگ 1

- راهنمای ساخت پادکست 1

- تقویم 1

- خط زمانی تاریخ/List of centuries 2

- دستور زبان/This page is a style 2

- نقطه گذاری/Manual of Style 2

- تاریخ اسلام 1

- تاریخ اروپا 1

- تاریخ امریکای لاتین 1

- تاریخ خاور میانه 1

- **شناسنامه بازیکنان تیم ایران*** 1

- جانورشناسی/Zoology 1

- گیاهشناسی/Botany 1

- زیستشناسی سلولی و مولکولی 1

- میکروبیولوژی 1

- ژنتیک / Genetics 1

- بیوشیمی / Biochemistry 1

- بیوفیزیک/Biophysics 1

- بیوانفورماتیک/Biophysics 1

- زیستفناوری 1

- ۱ اینترنت آینده (New generation 2

- ۳ نشانی آیپی 1

- ۳.۱ آی پیها دارای 4 کلاس هستند: 1

- ۳.۲ نام دامنه 1

- ۳.۳ DNS 1

- ۳.۴ پورت 1

- ۳.۵ پروتکل 1

- ۴ اینترنت امروزی 2

- ۶ فرهنگ اینترنت 1

- ۷ سایر موضوعات مرتبط 1

- ۸ نکات حقوقی و اخلاقی 1

- ۹ دسترسی به اینترنت 1

- ۱۰ جستارهای وابسته 1

- ۱۱ پیوندهای بیرونی 1

- روانشناسی یادگیری 1

- روانشناسی اجتماعی 1

- روانشناسی رشد 1

- روانشناسی بالینی 1

- روانشناسی تربیتی 1

- روانشناسی صنعتی 1

- روانشناسی دین 1

- روانشناسی خانواده 1

- روانشناسی جنایی 2

- روانشناسی تحلیلی (یونگ) 1

- روانشناسی کودکان استثنایی 1

- مهندسی برق 2

- مهندسی پزشکی 1

- مهندسی ژئوماتیک (نقشه برداری) 1

- مهندسی شیمی 1

- مهندسی صنایع 1

- مهندسی عمران 1

- مهندسی معدن 1

- مهندسی مکانیک 3

- مهندسی مواد 1

- مهندسی نساجی 1

- مهندسی نفت 1

- مهندسی نرمافزار 2

- مهندسی هوافضا 2

- مهندسی فناوری اطلاعات 1

- مهندسی شهرسازی 1

- فنّاوری اطلاعات /Information 1

- صنعت / Industry 1

- فناوری نانو / Nanotechnology 2

- زیستفناوری (بیوتکنولوژی) 1

- الگوریتم تورینه /Rete algorithm 1

- نانولولههای کربن/Carbon nanotub 1

- اخترفیزیک / Astrophysics 4

- کیهانشناسی / Cosmology 3

- فیزیک فضا / Cosmic physics 2

- فیزیک پلاسما / Plasma 2

- فیزیک اتمی 1

- فیزیک لیزر، / Laser 3

- نجوم / Astronomy 4

- نانو تکنولوژی/Nanotechnology 3

- فیزیک نظری/Theoretical physics 3

- بزرگان علم فیزیک 1

- گالیلئو گالیله / Galileo Galilei 3

- ایزاک نیوتن/Isaac Newton 3

- ترمودینامیک/Thermodynamics 3

- سعدی کارنو/Nicolas Léonard Sadi 2

- الکترومغناطیس/Electromagnetism 2

- مایکل فارادی/Michael Faraday 2

- ماکسول/James Clerk Maxwell 3

- مکانیک آماری/Statistical mechani 3

- نسبیت 1

- آلبرت اینشتین/Albert Einstein 4

- مکانیک کوانتومی/Quantum mechanic 4

- ماکس پلانک/Max Planck 3

- (نیلز بر) 1

- اروین شرودینگر/Erwin Schrödinger 3

- فیزیک هستهای 1

- ماری کوری /Marie Curie 3

- ارنست رادرفورد/Ernest Rutherford 4

- انریکو فرمی/Enrico Fermi 2

- بمب اتمی 1

- فیزیک ذرهای/Particle physics 3

- ادوین هابل/Edwin Hubble 3

- استیون هاوکینگ/Stephen Hawking 3

- anoshe ansari 1

- منشور کوروش و طرح یک سئوال 1

جدیدترین یادداشتها

همهنویسندگان

- سپهر 342

بایگانی

- مهر 1385 3

- تیر 1385 1

- خرداد 1385 338

Michael Faraday, FRS (September 22, 1791 – August 25, 1867) was a British chemist and physicist (who considered himself a natural philosopher) who contributed significantly to the fields of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. He also invented the earliest form of the device that was to become the Bunsen burner, which is used almost universally in science laboratories as a convenient source of heat.

Some historians of science refer to him as the greatest experimentalist in the history of science. It was largely due to his efforts that electricity became viable for use in technology. The SI unit of capacitance, the farad, is named after him, as is the Faraday constant, the charge on a mole of electrons (about 96,485 coulombs). Faraday's Law of induction states that a magnetic field changing in time creates a proportional electromotive force.

He held the post of Fullerian Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution of Great Britain.

Contents[hide] |

Early career

Michael Faraday was born in Newington Butts, near present-day Elephant and Castle in south London. His family was poor, his father, James Faraday, was a blacksmith and Faraday had to educate himself. At fourteen he became apprenticed to bookbinder and seller George Riebau and, during his seven year apprenticeship, read many books, developing an interest in science and specifically electricity.

At the age of twenty, in 1812, at the end of his apprenticeship, Faraday attended lectures by the eminent English (Cornish) chemist and physicist Humphry Davy of the Royal Institution and Royal Society, and John Tatum, founder of the City Philosophical Society. The tickets were given Faraday by William Dance (one of founders of the Royal Philharmonic Society). After, Faraday sent Davy a sample of notes taken during the lectures, Davy said he would keep Faraday in mind but he should stick to his current job of book-binding. After Davy damaged his eyesight in an accident with nitrogen trichloride, he employed Faraday as a secretary. When John Payne of the Royal Institution was fired, the now Sir Humphry Davy was asked to find a replacement for him, so that Faraday was appointed Chemical Assistant at the Royal Institution on 1 March 1813.

Faraday eagerly left his bookbinding job and his hot-tempered employer, Henry de la Roche.

In a class-based society, Faraday was not considered a gentleman. When Davy went on a long tour to the continent in 1813-5, his valet refused to go. Faraday was part of the party as Davy's scientific assistant, and was asked to act as Davy's valet until a replacement could be found in Paris. Davy failed to find a replacement, and Faraday was forced to fill the role of valet as well as assistant throughout the trip. Davy's wife, Jane Apreece, refused to treat Faraday as an equal (making him travel outside the coach, eat with the servants, etc.) and generally made Faraday so miserable he contemplated returning to England alone and giving up science altogether. However, it was not long before Faraday surpassed Davy.

He also was the first to link electricity to magnetism and then link magnetism back to electricity - i.e. he induced an electric current using magnets - thus inventing the dynamo, predecessor to today's electric generator.

Scientific career

His greatest work was with electricity. In 1821, soon after the Danish physicist and chemist, Hans Christian Ørsted discovered the phenomenon of electromagnetism, Davy and British scientist William Hyde Wollaston tried but failed to design an electric motor. Faraday, having discussed the problem with the two men, went on to build two devices to produce what he called electromagnetic rotation: a continuous circular motion from the circular magnetic force around a wire. A wire extending into a pool of mercury with a magnet placed inside would rotate around the magnet if supplied with current from a chemical battery. This device is known as a homopolar motor. These experiments and inventions form the foundation of modern electromagnetic technology. Unwisely, Faraday published his results without acknowledging his debt to Wollaston and Davy, and the resulting controversy caused Faraday to withdraw from electromagnetic research for several years.

At this stage, there is also evidence to suggest that Davy may have been trying to slow Faraday’s rise as a scientist (or natural philosopher as it was known then). In 1825, for instance, Davy set him onto optical glass experiments, which progressed for six years with no great results. It was not until Davy's death, in 1829, that Faraday stopped these fruitless tasks and moved on to endeavors that were more worthwhile.

Two years later, in 1831, he began his great series of experiments in which he discovered electromagnetic induction, though the discovery may have been anticipated by the work of Francesco Zantedeschi. He found that if he moved a magnet through a loop of wire, an electric current flowed in the wire. The current also flowed if the loop was moved over a stationary magnet.

His demonstrations established that a changing magnetic field produces an electric field. This relation was mathematically modelled by Faraday's law, which subsequently became one of the four Maxwell equations. These in turn evolved into the generalization known as field theory.

Faraday then used the principle to construct the electric dynamo, the ancestor of modern power generators.

Faraday proposed that electromagnetic forces extended into the empty space around the conductor, but did not complete his work involving that proposal. Faraday's concept of lines of flux emanating from charged bodies and magnets provided a way to visualize electric and magnetic fields. That mental model was crucial to the successful development of electromechanical devices which dominated engineering and industry for the remainder of the 19th century.

Faraday worked extensively in the field of chemistry, discovering chemical substances such as benzene, inventing the system of oxidation numbers, and liquefying gases such as chlorine. He prepared the first clathrate hydrate. Faraday also discovered the laws of electrolysis and popularized terminology such as anode, cathode, electrode, and ion, terms largely created by William Whewell. For these accomplishments, many modern chemists regard Faraday as one of the finest experimental scientists in history. Despite his excellence as an experimentalist, his mathematical ability did not extend so far as trigonometry or any but the simplest algebra.

In 1845 he discovered what is now called the Faraday effect and the phenomenon that he named diamagnetism. The plane of polarization of linearly polarized light propagated through a material medium can be rotated by the application of an external magnetic field aligned in the propagation direction. He wrote in his notebook, "I have at last succeeded in illuminating a magnetic curve or line of force and in magnetising a ray of light". This established that magnetic force and light were related.

In his work on static electricity, Faraday demonstrated that the charge only resided on the exterior of a charged conductor, and exterior charge had no influence on anything enclosed within a conductor. This is because the exterior charges redistribute such that the interior fields due to them cancel. This shielding effect is used in what is now known as a Faraday cage.

Later life

More that a half a century after a teenaged Faraday first visited the Royal Institution, he could still be found there, spending hours watching the sky from his window.

"Next Sabbath day (the 22nd) I shall complete my 70th year. I can hardly think of myself so old." — Faraday

During his lifetime, Faraday rejected a knighthood and twice refused to become President of the Royal Society.

He died at his house at Hampton Court on August 25, 1867. He is buried in Westminster Abbey, near Isaac Newton's tomb.

Miscellaneous

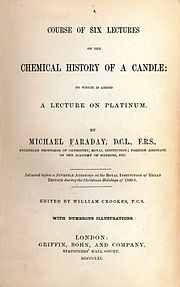

He gave a successful series of lectures on the chemistry and physics of flames at the Royal Institution, entitled The Chemical History of a Candle; this was the origin of the Christmas lectures for young people that are still given there every year and bear his name.

Faraday was known for designing ingenious experiments, but lacked a good mathematics education. (However, his affiliation with James Clerk Maxwell helped in this regard, as Maxwell was able to translate Faraday's experiments into mathematical language.) He was regarded as handsome and modest, declining a knighthood and presidency of the Royal Society (Davy's old position).

His picture was printed on British £20 banknotes from 1991 until 2001[1].

His sponsor and mentor was John 'Mad Jack' Fuller, who created the Fullerian Professorship of Chemistry at the Royal Institution. Faraday was the first, and most famous, holder of this position to which he was appointed for life.

Faraday was also a devout Christian and a member of the small Sandemanian denomination, an offshoot of the Church of Scotland. He served two terms as an elder in the group's church.

Faraday married Sarah Barnard in 1821 but they had no children. They met through attending the Sandemanian church.

Publications

- Faraday,Michael (1861). A Course of 6 lectures on the various forces of matter and their relations to each other. edited by William Crookes

References

- Hamilton, James (2002). Faraday: The Life. Harper Collins, London. ISBN 0007163762.

- Hamilton, James (2004). A Life of Discovery: Michael Faraday, Giant of the Scientific Revolution. Random House, New York. ISBN 1400060168.

- Thomas, John Meurig (1991). Michael Faraday and the Royal Institution: The Genius of Man and Place Hilger, Bristol. ISBN 0750301457

- Thompson, Silvanus (1901, reprinted 2005) “Michael Faraday, His Life and Work”. Cassell and Company, London, 1901; reprint by

Kessenger Publishing, Whitefish, MT. ISBN 1417970367

Quotations

- "Nothing is too wonderful to be true."

- "Work. Finish. Publish." — his well-known advice to the young William Crookes

- "The important thing is to know how to take all things quietly."

- Regarding the hereafter, "Speculations? I have none. I am resting on certainties. I know whom I have believed and am persuaded that he is able to keep that which I have committed unto him against that day."

External links and articles

Biographies

- Detailed biography of Faraday

- IEE biography of Michael Faraday

- Faraday as a Discoverer by John Tyndall, Project Gutenberg (downloads)

- The Christian Character of Michael Faraday

Others

- Michael Faraday Directory

- Works by Michael Faraday at Project Gutenberg (downloads)

- "Experimental Researches in Electricity" by Michael Faraday Original text with Biographical Introduction by Professor John Tyndall, 1914, Everyman edition.

- Video Podcast with Sir John Cadogan talking about Benzene since Faraday

Further reading

- Ames, Joseph Sweetman (Ed.), "The discovery of induced electric currents" Vol. 2. Memoirs, by Michael Faraday. New York, Cincinnati [etc.] American book company [c1900] LCCN 00005889

See also

- UK topics

- Faraday's Diary, ¶ 7718, 30 September 1845 and ¶ 7504, 13 September 1845

Michael Faraday, född 22 september 1791, död 25 augusti 1867, brittisk fysiker och kemist, som kom med viktiga bidrag inom elektromagnetism och elektrokemi. Han uppfann den tidigaste formen av det som kom att bli bunsenbrännaren, som används i vetenskapliga laboratorier i stort sett hela världen, som en källa för att snabbt få fram värme.

Faraday är en av historiens största vetenskapsmän, och det var mycket tack vare honom som elektricitet blev möjligt att använda inom teknologi. SI-enheten för kapacitans, farad, är döpt efter honom.

Tidig karriär

Faraday föddes i Newington i London. Hans far var smed, och familjen var relativt fattig, han fick därför utbilda sig själv. Vid fjorton års ålder blev han lärling till en bokbindare och försäljare vid namn George Riebau, och under sina sju år som lärling läste han många böcker och fick ett intresse för vetenskap och framför allt elektricitet.

Vid 20 års ålder deltog Faraday i föreläsningar hållna av sir Humphry Davy, ordförande i Royal Society, och John Tatum, grundare av City Philosophical Society. Efter att Faraday skickat en samling anteckningar till Davy sade Davy att han skulle överväga Faraday, men att han ändå borde hålla sig till sitt yrke som bokbindare. Efter att Davy skadat sina ögon i en olycka vid ett experiment med trikloramin anställde han Faraday som sekreterare. När John Payne vid Royal Society blev avskedad, rekommenderade Michael Faraday som laboratorieassistent. Faraday tog med glädje emot posten då hans nya arbetsgivare inom bokbinderiet ska ha haft ett hett temperament.

På grund av det klassbaserade samhället sågs Faraday inte som en gentleman, det sägs att Davys fru vägrade att behandla honom som jämlik, och tvingade honom att sitta hos tjänarna.

Vetenskaplig karriär

Faraday arbetade främst med elektricitet. 1821, kort efter att den danske kemisten Hans Christian Ørsted upptäckte fenomenet elektromagnetism försökte Humphry Davy och William Hyde Wollaston skapa en elektrisk motor. Faraday, som hade diskuterat problemet med de två männen, byggde två apparater som skapade vad han kallade elektromagnetisk rotation, det vill säga oavbruten cirkelrörelse med hjälp av den cirkulära magnetiska kraften runt en metalltråd. En metalltråd som ledde in i kvicksilver med en magnet inuti skulle rotera runt magneten om den laddats med elektricitet av ett kemiskt batteri. Apparaturen kallas homopolär motor. Dessa experiment och uppfinningar skulle bli grunden till den moderna elektromagnetiska teknologin. Faraday publicerade oklokt sina resultat utan att erkänna tacksamhetsskuld till Davy och Wollaston, och den kontrovers som uppstod på grund av detta fick Faraday att dra sig ur den elektromagnetiska forskningen i flera år.

Tio år senare, 1831, påbörjade han en lång serie experiment där han upptäckte induktion, även om upptäckten kan ha förutsetts av Francesco Zantedeschis arbete. Han upptäckte att om han rörde en magnet runt en snurrad metalltråd uppstod en elektrisk ström i tråden. Strömmen flödade också om tråden rörde sig över en stationär magnet.

Hans demonstrationer fastslog att ett ändrande magnetiskt fält skapar ett elektriskt fält. Relationen modellerades matematiskt i Faradays induktionslag, som blev en av Maxwells elektromagnetiska ekvationer.

Faraday använde principen för att konstruera den elektriska dynamon, föregångaren till den moderna kraftgeneratorn.

Faraday föreslog att elektromagnetiska krafter utvidgades in i det tomma området runt ledaren, men slutförde inte arbetet kring det förslaget. Faradays teori om linjer av ström som härrörde från laddade källor skapade ett sätt att visualisera elektriska och magnetiska fält. Den sinnesmodellen var avgörande för den lyckade utvecklingen av elektromekaniska apparater som dominerade ingenjörskap och industri under resten av 1800-talet.

Faraday sysslade också med kemi, och upptäckte kemiska substanser som bensen, uppfann oxideringsnumreringen, samt smältande gaser som klorin. Han upptäckte också elektrolysens lagar, och populariserade terminologi som anod, katod, elektrod och jon.

1845 upptäckte han det som idag kallas Faradayeffekten, det fenomenet döpte han till diamagnetism. Polarisationsplanet av linjärt polariserat ljus utökat genom ett materiellt medium kan roteras genom applicering av ett externt magnetiskt fält i utökningens riktning. Detta etablerade att magnetisk kraft och ljus var relaterade.

I sitt arbete med statisk elektricitet visade Faraday att en laddning bara leddes längs med utsidan av en laddad ledare, och att förändring på exteriören inte hade någon påverkan på det som var inuti ledaren. Denna effekt kallas idag för Faradays bur.